Verona, Italy

Future – 2025

In 1996, as an architecture student travelling through Italy, I longed to visit Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum in Verona — a project already spoken of in reverent tones as a defining moment in modern conservation architecture. But fate intervened: the... Read more

In 1996, as an architecture student travelling through Italy, I longed to visit Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum in Verona — a project already spoken of in reverent tones as a defining moment in modern conservation architecture.

But fate intervened: the Chernobyl disaster had just occurred, and as word reached us months later, our travel plans were upended.

Twenty-nine years later, I finally arrived. And the wait was worth every day of anticipation.

The Birth of Conservation Architecture

Scarpa’s 1964 transformation of the medieval Castelvecchio marked a turning point — a new language of restorative architecture that inserted finely crafted modern elements within a centuries-old structure.

Rather than restoring to an imagined past, Scarpa revealed the building’s life: the worn edges, the patched stone, the traces of human touch.

A Museum of Craft and Precision

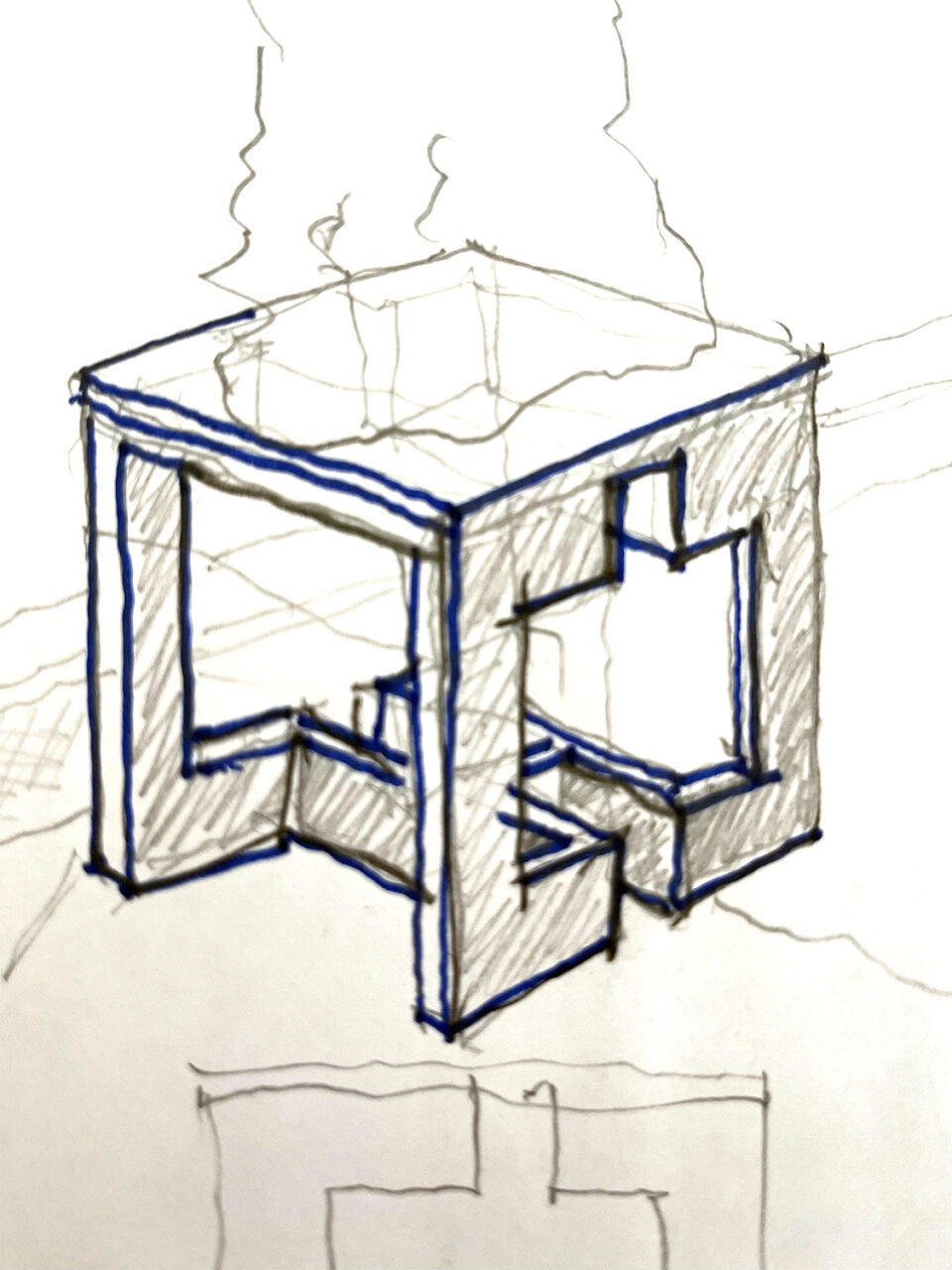

Wandering the galleries, I was struck by the sheer inventiveness of Scarpa’s curatorial architecture. Every object — from delicate jewellery to heavy armour — is supported, suspended, or framed by an element of design that feels both considered and deeply poetic.

Scarpa’s material language is a study in balance: cast concrete and brass, copper and timber, rough stone and polished surface.

Coloured concrete walls float freely within larger rooms, dividing space with sculptural intent.

Benches and plinths are not merely functional but proportioned with a kind of musical rhythm — their steel and timber in dialogue rather than hierarchy.

Everything is intentional, but nothing feels forced.

You sense an architect listening to material, adjusting, refining, until each element sits in quiet equilibrium.

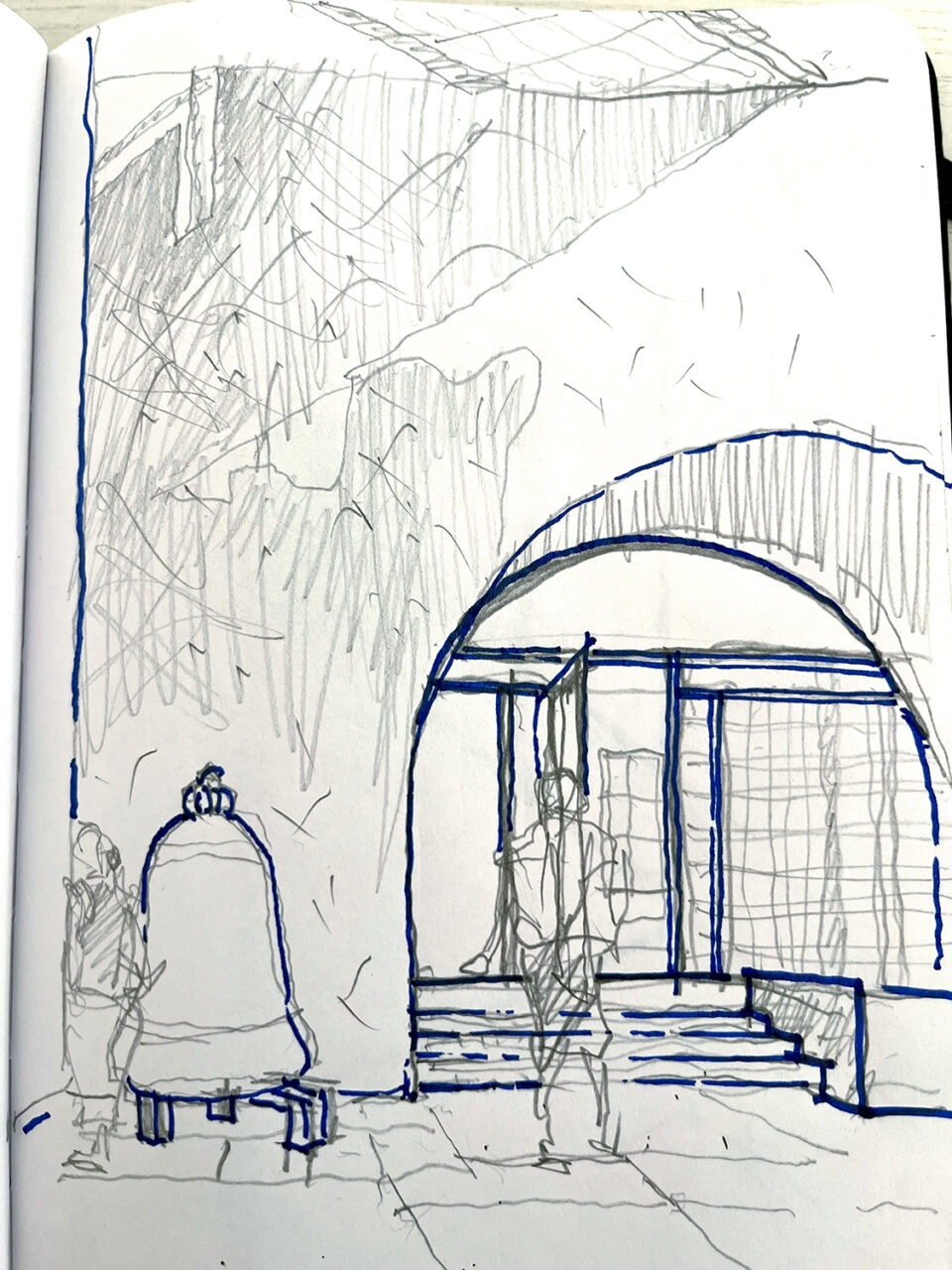

The Cangrande Moment

At the heart of the museum lies the iconic bridge and display platform for the equestrian statue of Cangrande della Scala.

Scarpa worked on its position for years — and it shows.

As you cross from one wing to another, the horse and rider appear mid-turn, caught in motion, their gaze following you as you emerge onto the bridge.

It’s a masterclass in spatial choreography — a meeting of sculpture, architecture, and human experience.

The Details That Teach

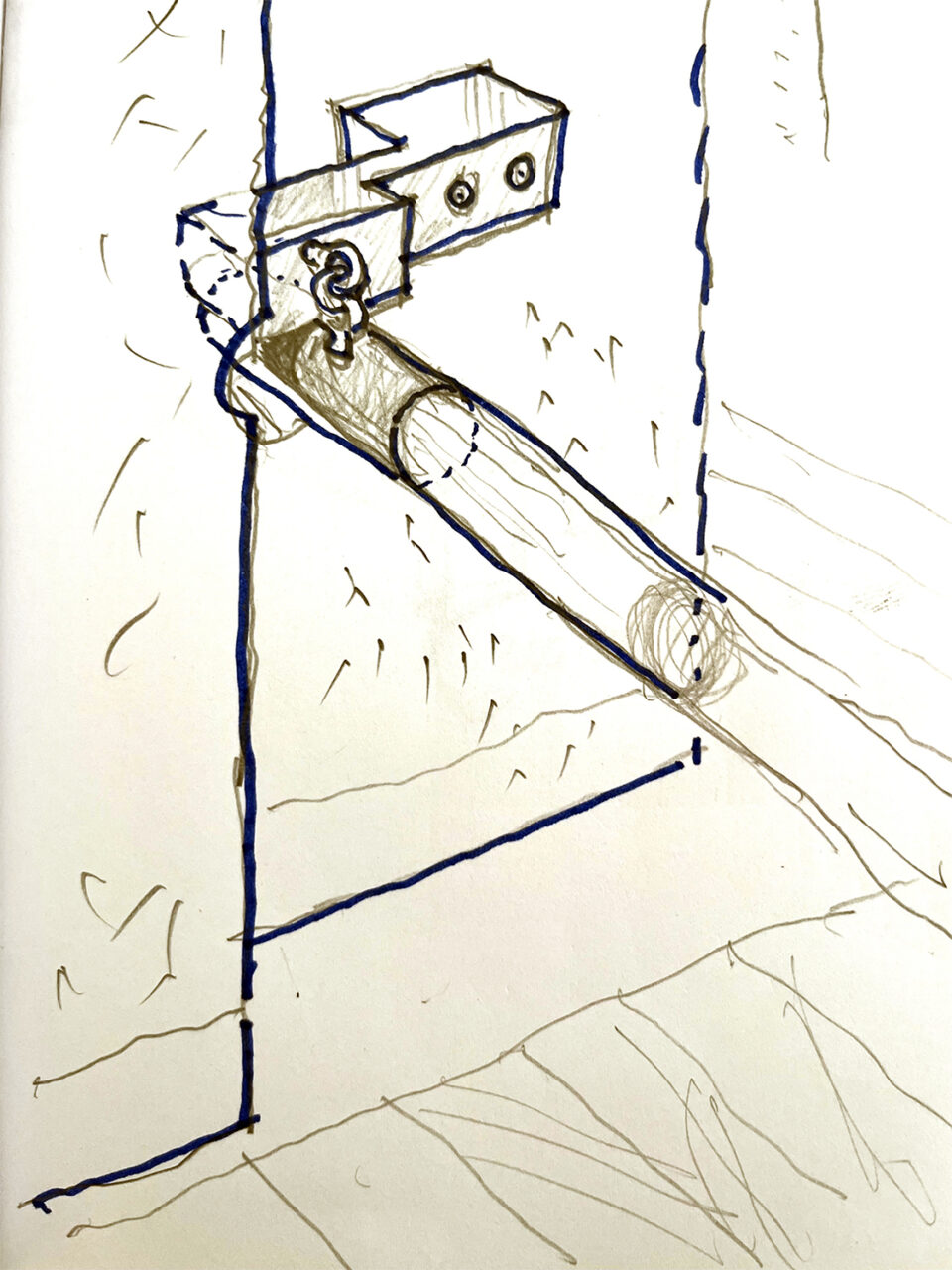

Scarpa’s detailing is both structural and spiritual.

A cantilevered stair floats just 50 millimetres above the floor, turning a step into a moment of levitation.

Another stair — now endlessly copied — folds sheets of Corten steel into ribbons, rising from wall to balustrade with no handrail to interrupt its purity.

Elsewhere, a narrow cast-concrete stair splits diagonally to manage a steep rise — defiant, compact, utterly resolved.

Material Interconnection: Design Across Scale

Scarpa’s philosophy of material interconnection reveals itself at every scale — from the grand to the granular.

In the pedestrian bridge linking the two main wings of the museum, this philosophy becomes structure: layers of stone, steel, and concrete interlock, their joins revealing rather than concealing how materials meet and rely on one another.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the same sensitivity is evident in small details: the brass rings supporting the balustrade stair- and guard- rails.

Scarpa shows us that design integrity is not measured by scale.

The same philosophy governs the placement of a massive bridge and the turning of a small brass fitting. Both carry the same reverence for material, craft, and the intimate collaboration between maker and material.

Windows as Modern Reliefs

Even Scarpa’s window frames are acts of meditation.

Brass screens, pivoting doors, and layered glazing are composed as if they were modern reliefs — abstract, rhythmic, and responsive to light.

Rough medieval stone arches meet razor-thin steel thresholds, and the result is not contrast but harmony.

Enduring Lessons

Leaving Castelvecchio, I felt renewed respect for the act of making.

Scarpa’s work is not about preservation or perfection — it is about empathy.

He teaches that materials can hold memory, that light is a form of storytelling, that design can invite participation rather than dictate experience.

His museum continues to breathe and evolve, alive in every polished brass edge and worn stone floor.

Reflection: Ongoing Joyful Experiences

Standing in those galleries, I understood why Castelvecchio resonates so deeply with me, and with the philosophy that underpins my own practice.

Scarpa’s architecture embodies what I call Ongoing Joyful Experiences — spaces that unfold gently through time, offering pleasure, surprise, and reflection in the smallest moments.

Like Scarpa, I believe architecture begins with people: with how we move, touch, sit, look, rest, and connect.

Scarpa reminds me that architecture at its best is not an act of control, but of care. It asks us to consider how light lands on stone, how a door pivots in the hand, how a stair invites a pause.

These are the moments that make buildings alive and the life within them joyful.

— Malcolm Taylor